Research Methods for Global Studies II (GLO1221)

Teaching material for Quantitative Methods track in Semester 1

Install your python environment

Tutorial 1

Tutorial 2

Tutorial 3

Tutorial 4

Tutorial 5

Tutorial 6

Tutorial 2

Tutorial Summary

Core topics:

- Recap of variables in Python programming

- Learn what modules are and how to import them

- Load data with pandas

Advanced topics:

- Perform different actions using conditional statements

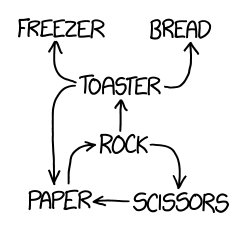

In this tutorial we are going to create a simple interactive game of Rock, Paper, Scissors. We’ll recap and extend some of the concepts from the last tutorial and introduce some new concepts such as importing modules and visualisation.

Variables (recap)

From the last tutorial, recall that variables have names and store data values. Variables are created when a value is assigned to it. We assign a value to a variable using the = symbol. The value on the right is assigned to the variable on the left.

variable_name = data_value

Variables must be created before they are used. If we try to use a variable before assigning a value, then Python will give us an error message. For example:

city = "Maastricht"

print(city)

print(country)

continent = "Europe"

print(Continent)

country = "The Netherlands"

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_80627/3477179379.py in <module>

1 city = "Maastricht"

2 print(city)

----> 3 print(country)

4 continent = "Europe"

5 print(Continent)

NameError: name 'country' is not defined

Error messages can look confusing at first glance, but they can help us understand what went wrong. It is important to try and understand error messages because you will see a lot of them! (Even experienced computer programmers get a lot of error messages.)

Exercise 1: Copy the code above into your notebook and run it to replicate the error message for yourself. Look carefully at the error message. What clues does the error message give about what went wrong? (What type of error? Where did the error occur? etc.)

Exercise 2: Correct the error that you identified. Is there another issue with the code? What is it?

Always remember that the order matters in Python. This also includes the order in which you run cells in your notebook!

Rock paper scissors (part 1)

We can use variables to start writing the code for our game of Rock, Paper, Scissors.

computer_selection = "Rock"

user_selection = input("Select: Rock, Paper, or Scissors")

Exercise 3: In your notebook add a line of code to display the two selections using the print() function and F-strings.

Remember F-strings have an f before the quotation marks, e.g.,

f"Some text to display {variable_name}"

if you need a reminder, then check the previous tutorial.

Importing modules

Last time we considered the idea of functions as pre-built tools that we may want to use in our code. Sometimes there are functions that exist but are not in the standard Python environment. To access other functions we need to import the module that contains them.

We can think of modules as being sets of related tools…

|

|

|---|---|

import SewingKit |

import PencilCase |

|

|

import MechanicalToolkit |

import Powertools |

For example, if you wanted to draw a picture but you didn’t have coloured pens, then you would need to go and get your pencil case. If PencilCase was a Python module, then we’d need to import PencilCase before we could use it.

Note that we only need to import a module once in a session. Much like a real pencil case, we only need to go and get it once and all the pens in the pencil case are available, until we put the pencil case back away.

For example, we can import the random module to access functions related to generating random numbers and choices:

import random

# Generate a random integer between 1 and 10

random_number = random.randint(1, 10)

print(f"Random number: {random_number}")

# Select a random snack

random_snack = random.choice(["chocolate", "apple", "cake"])

print(f"Random snack: {random_snack}")

Above, we see two examples of functions from the random module: randint and choice. Notice that when we run the function from a module, we need to tell python in which module the function can be found. We tell Python where to find a function using module_name.function_name()

Sometimes modules are organised into sub-modules, particularly when they are large modules… Imagine we have a really big stationary box organised into sections. If we want a red pencil then we will find it in the pencils section in the stationary box.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

BigStationaryBox.Pencils.RedPencil() |

||

| the RedPencil function is in the Pencils sub-module of the BigStationaryBox module |

The matplotlib module contains functions for drawing and plotting graphs and contains a sub-module that is also called pyplot in which we can find a function plot() to plot some data points in a graph.

import matplotlib.pyplot

# Data

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

y = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

# Create a simple line plot

matplotlib.pyplot.plot(x, y)

Again, this is all about telling Python where to find the function. We could have sub-sub-modules and sub-sub-sub-modules, e.g., module.submodule.subsubmodule.function()

Rock paper scissors (part 2)

So far the game is very easy to win because the computer always plays the same choice and you can see that choice.

Exercise 4: Create a new version of the game in which the computer_selection is chosen randomly from the possible options ["Rock", "Paper", or "Scissors"]

Using an alias

In Python, an alias refers to an alternative name or nickname given to a module. Aliases are handy because they allow you to use a shorter or more convenient name for something that might have a longer or more complex actual name. They make your code more readable and sometimes more concise. Aliases can be handy when you have to type out a module name many times.

To use an alias, we replace the module (or module.submodule) name with the alias. For example, we can instead import matplotlib.pyplot module as plt so that we don’t have to write matplotlib.pyplot every time we want to use a function from that module.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Here we have introduced the keyword as to indicate that we would like to use an alias.

Exercise 5: Adapt the code below so that it uses the alias plt.

# Data

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

y = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

# Create a simple line plot

matplotlib.pyplot.plot(x, y)

We’ll come back to visualisations in the next tutorial. For now, let’s load some data using the pandas module.

Pandas

Pandas is a powerful and widely-used data manipulation and analysis module in Python. It’s incredibly useful when you’re working with data. Whether you’re dealing with survey responses, economic indicators, or social demographics, Pandas provides you with the tools to load, explore, clean, and analyse data efficiently.

Before we can use Pandas, we need to import the module. Remember that you only need to run this once per session:

import pandas as pd

The pandas module mainly works with structured data. Structured data are data that we represent in a table in which there are rows and columns, where each row represents an individual observation or record, and each column represents a different attribute or variable. In pandas such a “table” is a new data type called a DataFrame.

Each column in a DataFrame has a label or name, which is used to identify and access that specific column. A DataFrame has an index that labels each row. The index can be a sequence of numbers, custom labels, or even dates, and it helps identify and retrieve specific rows. A DataFrame is designed to hold data of the same data type within each column.

Here’s a simple example of what a DataFrame might look like:

Name Age City

0 Alice 25 NYC

1 Bob 30 LA

2 Carol 22 Chicago

3 David 28 Boston

In this DataFrame, each row represents a person with attributes like Name, Age, and City. The column labels (Name, Age, City) are used to identify and access specific attributes.

Read data files with Pandas

The Pandas library makes it easy to load structured data from a file. Computer files come in different formats that tell the computer how to read them. We will use CSV format files. CSV stands for Comma Separated Value. A CSV file is a text file in which values are separated by commas. We usually identify CSV files by the .csv at the end of the filename (although sometimes a different ending is used and will also work, e.g., .txt).

For example the DataFrame above could be saved as a CSV file:

Name, Age, City

Alice, 25, NYC

Bob, 30, LA

Carol, 22, Chicago

David, 28, Boston

- Loading Data from a Local Source (e.g., your computer):

To load a CSV file from your working directory you can use the

read_csv()function:# Load a CSV file from your local computer data = pd.read_csv('your_file.csv')Replace

'your_file.csv'with the actual file path and name. If you installed Anaconda with default settings, then your working directory will likely be:- Windows 10:

C:\Users\<your-username>\Anaconda3\ - macOS:

/Users/<your-username>/anaconda3

So you can use the full path, e.g., on windows:

# Load a CSV file from your local computer data = pd.read_csv('C:\Users\<your-username>\Anaconda3\your_file.csv')You can then change the path to somewhere else on your computer, e.g.,

C:\Downloads\your_file.csv. - Windows 10:

-

Loading Data from a Remote Source (e.g., the internet): To load data from a remote source, you can use the same function, just change the file path and name with the URL:

# Load data from a remote CSV file url = 'https://example.com/your_data.csv' data = pd.read_csv(url)Replace

'https://example.com/your_data.csv'with the actual URL of the data you want to load.

In both cases above we have read the CSV file and stored it as a Pandas DataFrame in a variable called data. Don’t forget that you can name the variable (almost) anything you like and it’s best if you name it something meaningful, e.g., population_dataframe.

Note that if you provide the wrong location for the file or wrong file name then you will get an error.

url = 'aFileThatDoesNotExist.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(url)

---------------------------------------------------------------

FileNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-11-5b3ae3a38afe> in <module>

1 url = 'aFileThatDoesNotExist.csv'

----> 2 df = pd.read_csv(url)

Note that as far as python is concerned, a typo is the same as the wrong location or file name!

Exercise 6: Why does the error message indicate that there is a problem with the second line of code and not the first?

Exercise 7: Read the data from the introduction survey into a variable gs_intro_survey.

url = 'https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vTEX2jqDTG_1uLK6lc1jxhsLQd47DSpVDOQH4MOqk0LJXoDXxWvc68ozzUafm_LlDPUqwV6CHEc8AvO/pub?gid=267912267&single=true&output=csv'

View the data in pandas

You can use the head() function of a dataframe to display the first few lines of the dataframe and the columns property to see a list of columns.

Exercise 8: Use gs_intro_survey.head(5) to view the first five entries of the survey. Then change the code to display the first 10 entries.

Exercise 9: What is different about this function compared to previous functions we have encountered?

Exercise 10: Use gs_intro_survey.columns to display the questions of the survey. Why do you think that we do not include brackets () after .columns?

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Use pandas to read and analyse data1 |

Conditional statements (ADVANCED)

In Python, if statements are used to make decisions in your code based on certain conditions. They allow you to execute different blocks of code depending on whether a condition is True or False. Here’s a very basic introduction to if statements:

# Simple if statement

age = 19

if age > 18:

print("age is greater than 18") # Run the indented lines when

print("you can have a beer") # the condition is True

In this example:

- We define a variable

ageand assign it the value19. - We use an

ifstatement to check ifageis greater than18. - If the condition (

age > 18) isTrue, the indented block of code following theifstatement is executed.

To evaluate if a condition is True or False we use conditional operators:

| Operator | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

== |

Equal to | 5 == 5 |

True |

!= |

Not equal to | 5 != 3 |

True |

< |

Less than | 3 < 5 |

True |

> |

Greater than | 5 > 3 |

True |

<= |

Less than or equal to | 3 <= 5 |

True |

>= |

Greater than or equal to | 5 >= 5 |

True |

Sometimes we want Python to do something else if a condition is False. To do this we use an if-else statement:

# if-else statement

age = 17

if age > 18:

print("age is greater than 18")

print("you can have a beer")

else:

print("age is not greater than 18") # Run these indented lines when

print("you cannot have a beer") # the condition is False

In this example:

- We define a variable

ageand assign it the value17. - We use an

ifstatement to check ifageis greater than18. - If the condition (

age > 18) isTrue, it executes the code block underif. Otherwise, it executes the code block underelse.

Exercise 11: What happens when age = 18? Is this the correct outcome? How could you correct the code?

Sometimes we want to test a sequence of conditions. Then we can nest if statements by including another if-else statement within an if block or an else block.

For example, you want to check people are old enough to buy beer. However, you only want to ask for ID if they are close to the legal age.

age = int(input("What is your age:"))

if age > 25:

print("You can have beer")

else:

print("You need to show ID")

if age > 18:

print("You can have beer")

else:

print("You are not old enough for beer")

Nesting if statements can get a bit messy. An alternative is to use elif, which simply means else if. We can re-write the above code using an elif statement:

age = int(input("What is your age:"))

if age > 25:

print("You can have beer")

elif age > 18:

print("You need to show ID")

print("You can have beer")

else:

print("You need to show ID")

print("You are not old enough for beer")

Exercise 12: Try the above code in your notebook. Confirm that both give the same answer. How does the operation of the code change if you change the order of the conditions, e.g., swap the 18 and 25?

Rock paper scissors (part 3)

It would be nice for our game of Rock, Paper, Scissors to tell the user who has won the round. We can do this with conditional statements.

Exercise 13: Use conditional statements to update your code to correctly determine the result of the round of Rock, Paper, Scissors (win/lose/draw).

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Rock, Paper, Scissors, Toaster, Freezer, Bread2 |

-

AI generated image using Canva. ↩

-

from xkcd licensed under CC BY-NC 2.5 ↩